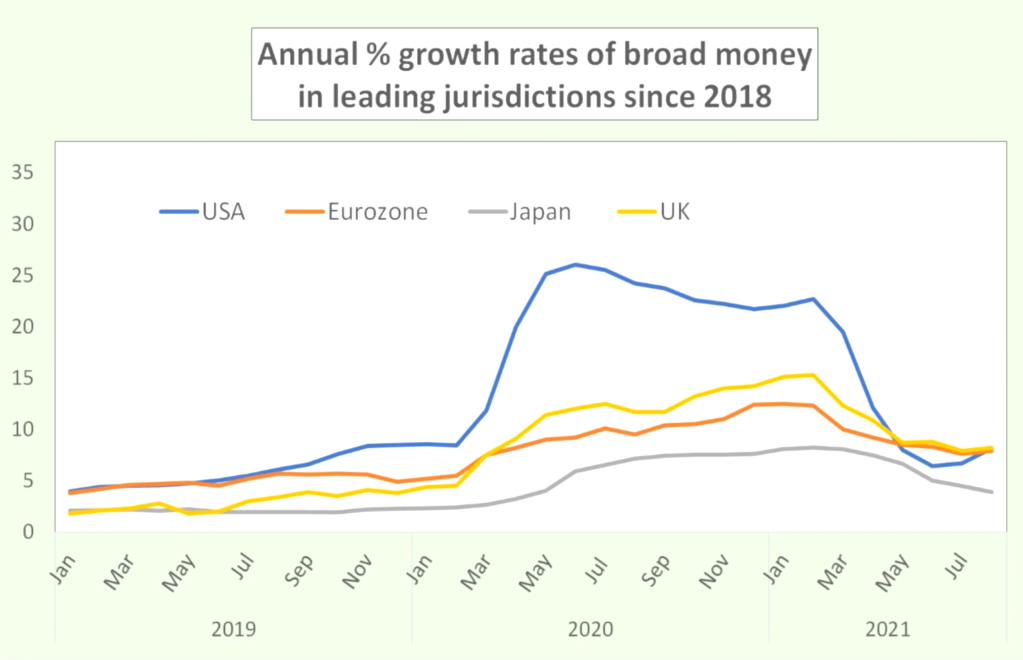

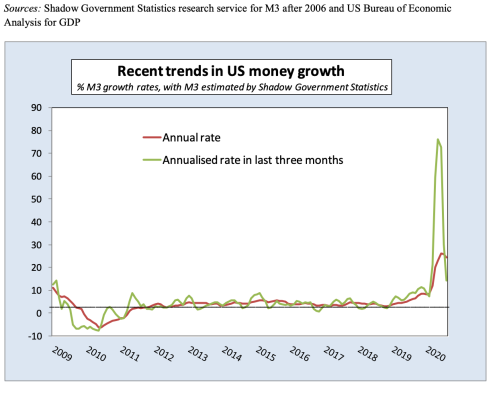

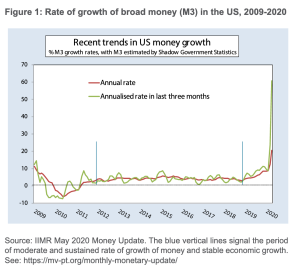

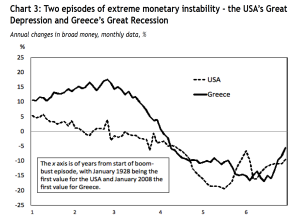

Last week, in an event organised by the IEA, my colleague from the IIMR, Tim Congdon, and myself stressed that annual money growth (broadly defined) must return to under 5% to bring inflation down to 2% a year. According to the latest monetary data available, the US, the Eurozone and the UK do not fulfil this condition. As reported by IIMR in its January 2022 money update (see table below), broad monetary growth in the US has accelerated in recent months, with an annual 9.8% rate of growth of M3, a figure well above that compatible with 2% price stability. In the Eurozone, monetary growth (M3) has also accelerated recently and is also too high (7.3% annual growth). The same applies to the UK (6.9% annual growth in broad money), though in this case the rate of growth of M4x has decelerated in the last few months.

Broad monetary growth world-wide

Here you will find two videos with our inflation forecasts for the US and the UK. In both cases, we use the quantity theory of money as the theoretical benchmark to make our analysis and projections of inflation for 2022- 2024. As Milton Friedman put it, there are “long and variable” lags between money growth and inflation. This is why, even if money growth fell to under 5% a year in the next few months, these lags mean that 2022, and probably 2023, will see inflation in the 5 per cent – 10 per cent area. This is because of the excess in money balances created in 2020 and 2021. Bringing inflation back to the central bank definition of price stability is a task for the medium term. Of course, ultimately the rate of inflation in the next two or three years will very much depend on the reaction central banks will take in the next few months to the current inflation episode.

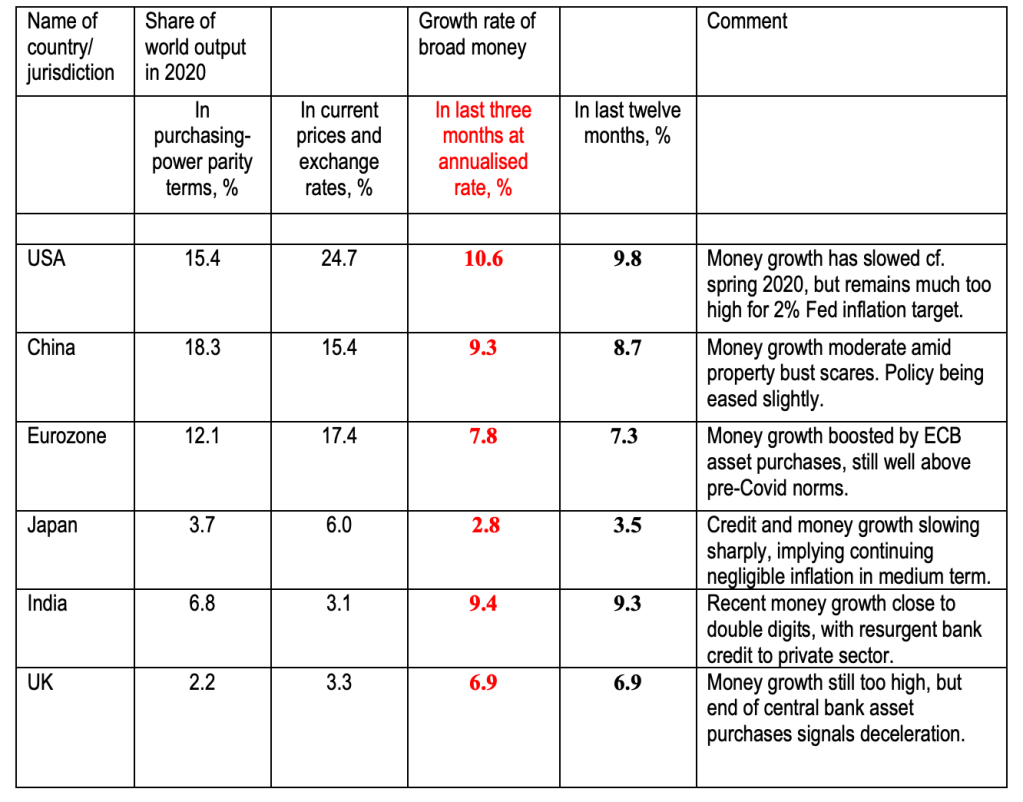

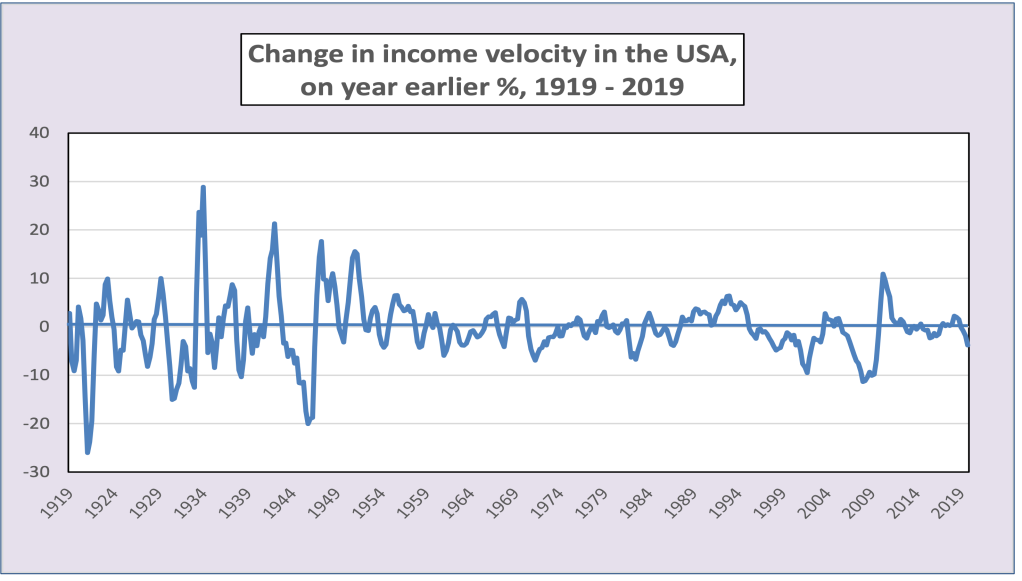

We used this same approach in a report written for the IEA in the spring 2020 when Tim Congdon and myself anticipated an inflation boom in the US in 2021-2023. A key element in our analysis and forecasts is that changes in money velocity revert to their mean, as the data shows (see below the reversion to the mean pattern observed in the US in the last century). This means that the surge in the demand for money (and thus in money velocity) in 2021 will gradually cease as it has started to happen and eventually return to its 2019 levels, therefore pushing spending and prices up. More details in the presentation on the US below.

The video presentation on the US inflation forecast comes from our contribution to the IIMR 2021 conference (“The 2020 money supply explosion and ensuing inflation”) and our comments on the UK from a recent interview we had with the IEA Head of Public Policy, Matthew Lesh.

Comments welcome.